In the week leading up to the release of George W. Bush’s memoir, reviewers chimed in with their opinions, hoping to define what the memoir means to the millions who read reviews instead of books.

In the week leading up to the release of George W. Bush’s memoir, reviewers chimed in with their opinions, hoping to define what the memoir means to the millions who read reviews instead of books.

Some said Bush is as stubborn as ever, insisting that history will show him in a kind light despite evidence to the contrary. Some found factual errors and highlighted them. Some longed to return to Bush’s presidency.

No review I read, however, pointed out my deepest feeling after reading Decision Point: the book is profoundly surreal.

Here is a president who defined his career by his decisiveness. The guy actually called himself “The Decider.”

Yet, reading his memoirs, I got the distinct impression that Bush never really made a decision in his life. Whether it’s following his dad’s example or listening to his close advisers, Bush’s own words gave me the impression that he is a man who floated through life and happened to become the president of the United States of America.

He went to two Ivy League schools, seemingly just because he had connections and wasn’t sure what he wanted to do with his life anyway. He got mediocre grades in both schools. Then he drifted for a decade or so, doing some labour and starting the occasional unsuccessful business. Then he got married and decided owning a baseball team would be fun. Then he ran for governor, and eventually for president.

Perhaps others will read it differently, but to me Decision Points reads like the memoir of a trust fund kid who happened to stumble into the presidency. Bush comes across as sincere, as someone who loves his family and took his responsibilities seriously, but if you’re looking for deep reflections on the use of power in the 21st century look elsewhere.

And if you’re looking to learn from someone who lived intentionally, who took control of his fate and made the most of it, Decision Points is not a book I’d recommend.

***

It’s September 11, 2001. I’m starting grade 11 at a small Christian high school in Ontario. The first class of the day is history, and we’re talking about what history is.

Mr. Korvemaker is one of those teachers who teaches best when he asks questions, and today is no exception. Everything he asks prompts conversation as we try to figure out what, exactly, history is.

What becomes history, what doesn’t become history? Is it the moments of the past that we, as a civilization, assign value to? Or are there some moments that are just intrinsically historic?

We are well into the conversation when we are interrupted by the PA system. Planes crashed into both World Trade Center towers in America, and no one is really sure what’s going on. Our vice principal, a lifelong educator typically sporting a sincerely happy demeanor, is fighting back tears. We later learn he has a friend working in one of the towers.

It seems insane, in retrospect, that our discussion about what history is could take place during a moment destined to go down in it.

***

“Where were you when it happened” stories have become a genre. Telling these stories is a sort of religious ritual, one in which the storyteller places their lives in the context of history.

Bush’s memoir contains this ritual early on.

He describes how he started his day on September 11, 2001. Reading the Bible, jogging, showering, breakfast, CIA briefing. His manner of describing everything is downright ordinary.

Most people know where Bush was when the planes hit: promoting his education reforms, reading to children in the Emma E. Booker Elementary School of Florida. It was a press-oriented visit, meant to boost No Child Left Behind.

His chief of staff whispered in his ear after both plane crashes. Bush kept reading.

“I saw reporters at the back of the room, learning the news on their cell phones and pagers,” he writes. “Instinct kicked in. I knew my reaction would be recorded and beamed throughout the world. The nation would be in shock; the president could not be. If I stormed out hastily, it would scare the children and send ripples of panic throughout the country.”

And so continuing to read a children’s book is heroic.

Not that I think he reacted poorly. On the contrary, I would do the same thing under the same circumstances. That’s not the point.

He shouldn’t have been doing the press-oriented school visit in the first place.

Modern presidents are pundits as well as politicians, a long tradition but one we should question. More would get done if politicians stopped campaigning once elections concluded. That Bush was promoting his work instead of working when the planes hit is a symbol of how out-of-sync with reality the modern presidency is.

Bush describes the rest of his day, riding Air Force One from location to location. Like most of us, he had no idea what was going on. He kept calling Washington to find out, but the entire government seemed to be in chaos. It was hours before he found out Al-Qaeda was to blame, at least by his telling.

The entire time Bush kept telling his people he wanted to get back to the White House, but for safety reasons this was continually delayed.

He made it eventually.

“Landing at Barksdale felt like dropping onto a movie set,” says the most powerful man on earth about seeing his own air force in action.

What a mediated world we live in.

***

It’s November, 2003. I’m halfway through my first semester at an small Christian university in Michigan. I’m figuring out what identity politics is.

Growing up in Canada ideology wasn’t something I thought of much. Mom and Dad voted against each other during a couple of elections, and it was more a joke than a fight.

Not so in Michigan, I soon learn. Here many accept political affiliations as though they are born into a caste.

“I’m a genetic Republican,” I hear more than once. A friend of mine explains she is a Democrat because of her New England upbringing.

This makes very little sense to me. What do ideas have to do with genetics or upbringing?

I take everything in stride, but a few things confuse me so much that I have to question them. Among them is a picture I see every day.

The picture is on the door of the dorm room across the hall from mine. It features a soldier manning a large gun in a desert, with a caption I never forgot:

“You aren’t the ones taking bullets in the desert. SUPPORT YOUR COUNTRYMEN.”

I was never against supporting troops. God knows I don’t envy them their job.

But that was rarely the purpose of signs like this in the early days of the Iraq war. The argument that one should support the troops was frequently twisted into a means of telling people to support the war in Iraq.

I reject this logic completely. One does not necessarily need to support a war just because there were troops fighting; that would mean accepting any war regardless of its morality.

So I write an article about America invading Canada to make this point. It probably convinces no one of anything, but I have fun with it.

I found a new passion: writing.

By the end of that year I write a regular satirical column in the student paper.

***

The Iraq war, through Bush’s telling, was completely logical. Saddam was a dick. Saddam ignored international law. International organizations were unwilling to do anything about this. America, and her allies, did it without their consent. Now Iraqis are voting, and the world is a better place.

This telling isn’t completely out of touch with reality. Saddam had been ignoring, and gaming, international law for decades much like North Korea and Iran do today.

Opponents of the war never argue these points. They argue that America doesn’t have the right to ignore the institutions, like the UN, which she built to make the world a better place. To hear Bush speak of the UN, however, you’d think it was just a conspiracy to stop America from properly taking care of everyone.

The war ended up being much longer than Bush imagined. Of course it cost the American economy billions. But to Bush, this is justified because the cause was just and the security of America depended on victory.

Ideological arguments like this will probably give way to reality in the coming century, as America’s wealth faces limits. Wars will be opposed on fiscal rather than moral grounds. America will no longer have the means to impose its order on the world, whether it wants to or not.

All of these arguments will look very different by then.

***

It’s April, 2005. My second year at Calvin is winding down, and I’m helping the staff at the student paper put the final touches on its annual parody issue.

The parody issue has a half century of mocking the school’s status-quo behind it, something we’re all aware of as we put all of our spare time into this year’s project. Editors have been fired, donations have been pulled and the school has more than once been forever changed for the better.

Simply put: truth is good. If God is good, falsehoods should be mocked. Parody is our way of mocking falsehoods, a responsibility we take very seriously.

This year we’re doing a mock version of People magazine, and it’s been exhausting. The layout is a pretty good recreation and the articles cover everything from closeted homosexuals to the hubris of certain communications professors.

Finally we think it’s finished and we’ll be able to go to bed at night instead of staying up working on the publication.

It’s not meant to be. The morning we wrap it up there is an announcement: George W. Bush will speak at our college’s commencement this year.

Well shit. Now we need to throw something about Bush into there. The exhaustion, however, eventually turned into school-child giddiness as we worked on our last-second addition to the publication.

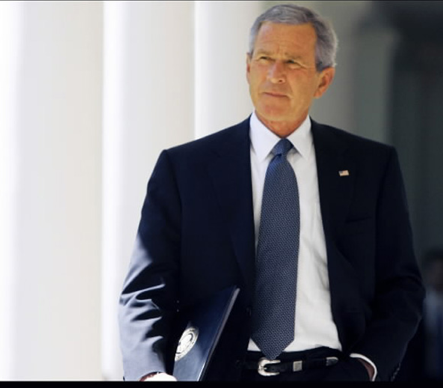

The design we eventually settled on felt nothing short of genius. Our collective minds, as though one, choose the famous cowboy image of Bush on his ranch and turned it into a parody Marlboro advertisement.

“Come to where the Savior is,” it read, “Come to Bush country.”

We intend to point out the sacrilegious overlap of religion and politics in contemporary America. Bush was the ultimate symbol of that, only highlighted by his decision to speak at our Christian university.

We also think our ad is hilarious.

***

History’s always been a nebulous concept, leading at least one 20th century automaker to call it “bunk.”

That being said, most people don’t spend our days wondering how history will judge them. For the most part, the average person assumes nothing they ever do will be taught in classes later on in life.

George W. Bush felt he had no such luxury. Late in his presidency Bush more than once mentioned his belief that history would vindicate him; that his current unpopularity is a momentary thing.

It makes sense, then, that the very first thing Bush mentions in his book is how important his book will be for future historians.

Maybe it’s because I’m young.

Maybe it’s become I came to political consciousness in Canada, where the stakes are so much lower, before moving to America.

Maybe it’s because nothing Bush did every really made sense to me at the time.

Whatever the reason, I can’t really describe Decision Points using any word besides surreal.