Writing isn’t just my job—it’s how I think. When I’m not sure what I feel about something I start typing. I put down ideas, contemplate whether I agree with what I just wrote, and in this process figure out how I feel.

A lot of my blog posts start as me playing around with ideas. Most such documents never end up published, though, because the point isn’t the content—it’s the process of writing itself. Writing, for me, is a practice—a skill I improve over time and use to understand the world.

Lately I’ve been trying to put a finger on why I hate so much of the rhetoric that surrounds AI, and I think the answer is related to the human art of practice. I’ve been struggling to put this into words until I saw a Bluesky post by Sam Halpert paraphrasing a Ted Chiang article about AI in the classroom. From that article:

Using ChatGPT to complete assignments is like bringing a forklift into the weight room; you will never improve your cognitive fitness that way.

This metaphor really clarifies things. We all know that using machines to do physical tasks doesn’t count as exercise. The same things applies to our minds. Asking an AI to write about a topic isn’t the same as going through the process of writing. Sure, AI might be capable of writing a blog post not that different from the one you’re reading now. What AI can’t do, though, is give me the intellectual experience of thinking through these ideas. And that intellectual experience isn’t just some annoyance that’s slowing down my writing output—it’s the entire point of writing itself.

I’m reminded of that AI CEO who thinks making music isn’t fun. Here’s what he said:

It’s not really enjoyable to make music now. It takes a lot of time, it takes a lot of practice, you need to get really good at an instrument or really good at a piece of production software. I think the majority of people don’t enjoy the majority of the time they spend making music.

Put aside, for now, that millions of people make music entirely because they enjoy doing so, and focus on his reason for saying people don’t enjoy it: because it takes practice. The assumption here is that we all want to skip the practice and get to the good part. This idea fundamentally misunderstands what it means to be human. The challenge of learning an instrument isn’t a barrier to enjoying making music—it’s a key part of why people like making music. You notice there’s something you can’t do and you spend time practicing until you can do it. That progress is rewarding because we are wired, as humans, for self improvement. Improving skills, over time, is enjoyable. So is using those skills to create.

This isn’t just true in the arts, or academic pursuits. It’s true in recreation. Take video games. These are fun because they offer challenges and give you a chance to get better at facing those challenges. The first time you play a Mario game you are going to run into every Goomba and fall into every pit. The fun comes when, on the second play-through, you get a little bit further than last time. The better you are at a game the more you crave difficulty, which is why games always get more challenging as you make progress.

Human flourishing demands these kinds of learning curves. Practice isn’t a barrier to enjoying life—it’s an essential tool for doing so. Technologists would do well to keep this in mind and think about how their tools can enable, not replace, this kind of learning and self improvement.

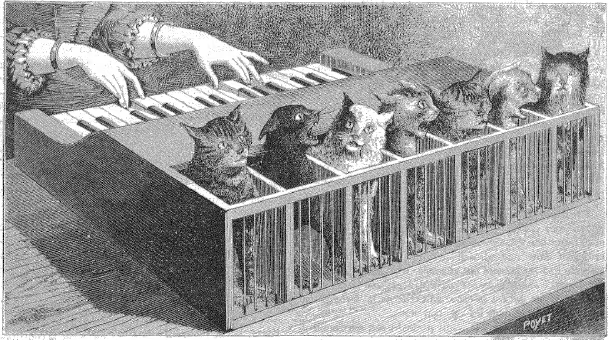

featured image of cat piano via Public Domain Review

2 responses to “Practice Is The Point”

I always found it odd that some of the first tasks we wanted AI to do are creative tasks. These are the tasks that are enjoyable to people. Writing, making music or doing graphic design are all manifestations of human creativity. Not sure why they didn’t use AI to take over unpleasant things we do as humans. Or just realize that the act of doing the tasks keeps us human. If machines did everything, then what would we be left to do?

@JustinPotBlog the world for humans and nature, not robots